Waves: What are They?

Author

Uncredited- Publication

- Surfing Illustrated (Winter 1962) - Volume 1, Issue 1

- Year

- 1962

Oceanographers have a lingo all their own, for waves. They speak of the “fetch” which is the distance a wave travels from the place it originates to where it meets its first obstacle. This may be thousands of miles. The wave’s “height” is measured from the trough to the crest, and its “length” is the distance from its crest to that of the next one. The “period” of a wave is the time required for the crest to pass a point reached by the one ahead of it. The height, length and period all have a relation to the fetch, the power of the wind which originates the wave, to the water’s depth, and to several other factors—volcanic eruptions, a sudden sinking of the ocean floor, or by glaciers pushing icebergs out to sea.

A wave does not advance across the ocean as a wall of water; it is an invisible force which itself moves and simply lifts the water as it passes along. Waves can be traced halfway around the world. Some of the rollers which break on the southwestern corner of England have come from Cape Horn, a fetch of more than 6,000 miles!

Reports of waves being over 100 feet high have been met with skepticism, but such waves have happened. An accurate observation was made in the Pacific aboard the USS Ramapo in February 1933. Substantiated by trigonometric calculations, the wave was logged as being 112 feet above its trough. This, to our knowledge, is the largest wave recorded, but by no means was this the most destructive.

On May 22, 1960, a section of the ocean floor collapsed during an earthquake, sucking millions of gallons of water into its cavity, and creating waves which rose to a height of 100 feet, traveling four hundred and fifty miles per hour. In Hilo, Hawaii, the wave front smashed three hundred yards inland, leveling a mile of waterfront. This tidal wave or tsunami also struck Japan, destroying 250 homes. Along one hundred miles of California coast, it caused $500,000 worth of damage.

In 1946, Hawaii was hit by a tsunami caused by an underwater earthquake two thousand miles away. The waves were only 25 feet high, but traveled at a speed of 470 miles per hour, roaring inland to destroy a great deal of property. In 1755, a quake in Lisbon caused a wave 80 feet high, which killed 100,000 people. In 1896, a huge Pacific wave swamped Japan, killing 28,000 people. Perhaps the greatest catastrophe was caused by the waves created by a hurricane, which hit the Bay of Bengal in 1737, destroying 28,000 boats and killing 300,000 people.

The force of a wave has been recorded as being as much as 6,000 pounds per square foot. It is little wonder that waves have destroyed homes, twisted railroad tracks, swept cars and buildings out to sea, and have tossed 10,000-pound stones over 20-foot sea walls!

Hurricanes do not produce the highest waves, for the wind tears off the tops of the crests; a four-mile-an-hour breeze will stir up real waves, but waves can only grow to a height of about one seventh the distance between crests without toppling in foaming whitecaps. The old sailor’s tale that the seventh wave is the one to watch out for is strictly a myth. There is absolutely no rule. The average speed of an ocean swell is about 35 miles an hour in the Pacific Ocean, and not quite so fast in the Atlantic, where the fetch is shorter.

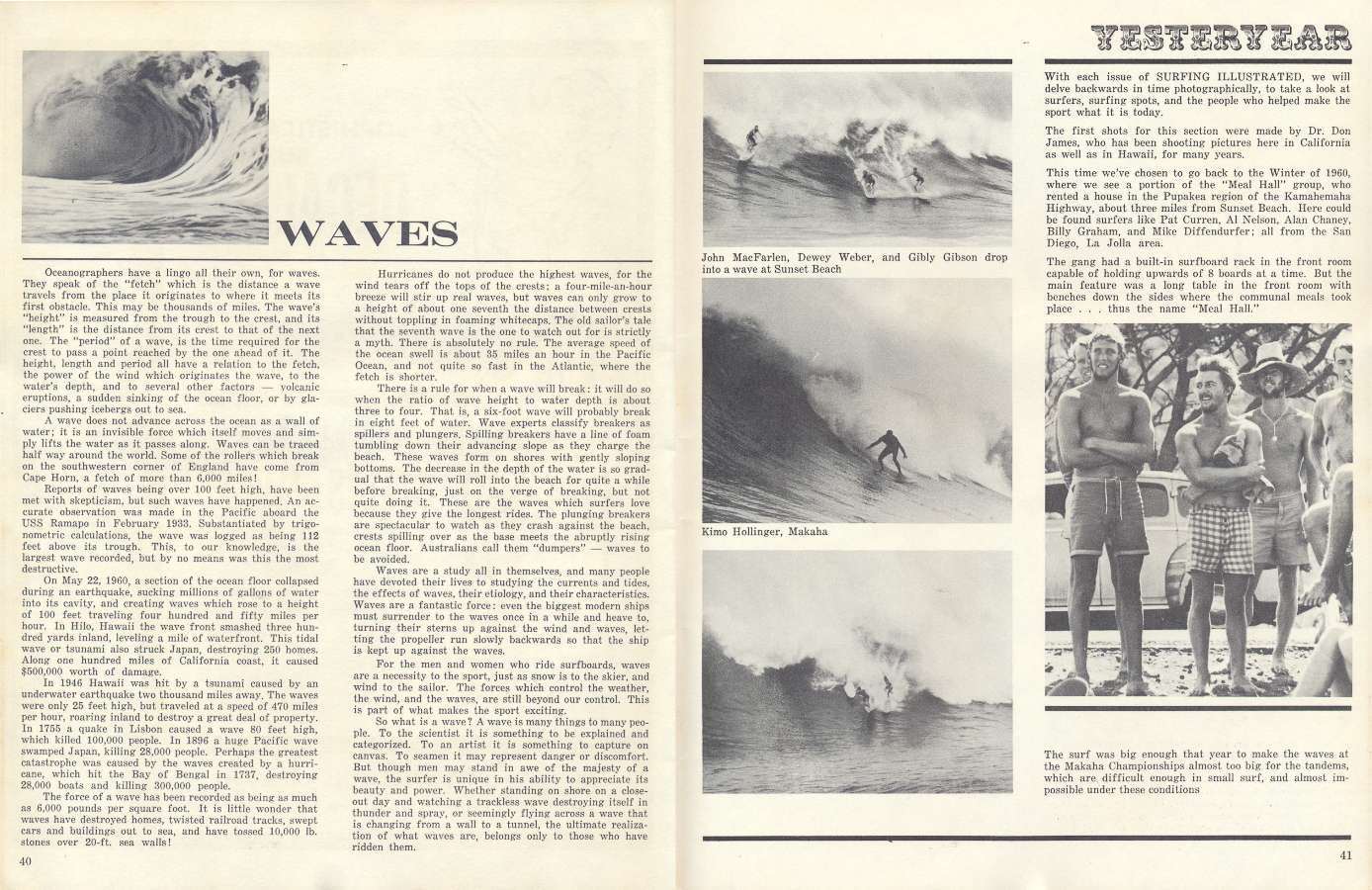

There is a rule for when a wave will break: it will do so when the ratio of wave height to water depth is about three to four. That is, a six-foot wave will probably break in eight feet of water. Wave experts classify breakers as spillers and plungers. Spilling breakers have a line of foam tumbling down their advancing slope as they charge the beach. These waves form on shores with gently sloping bottoms. The decrease in the depth of the water is so gradual that the wave will roll into the beach for quite a while before breaking, just on the verge of breaking, but not quite doing it. These are the waves which surfers love because they give the longest rides. The plunging breakers are spectacular to watch as they crash against the beach, crests spilling over as the base meets the abruptly rising ocean floor. Australians call them “dumpers”—waves to be avoided.

Waves are a study all in themselves, and many people have devoted their lives to studying the currents and tides, the effects of waves, their etiology, and their characteristics. Waves are a fantastic force: even the biggest modern ships must surrender to the waves once in a while and heave to, turning their sterns up against the wind and waves, letting the propeller run slowly backwards so that the ship is kept up against the waves.

For the men and women who ride surfboards, waves are a necessity to the sport, just as snow is to the skier, and wind to the sailor. The forces which control the weather, the wind, and the waves, are still beyond our control. This is part of what makes the sport exciting.

So what is a wave? A wave is many things to many people. To the scientist it is something to be explained and categorized. To an artist it is something to capture on canvas. To seamen, it may represent danger or discomfort. But though men may stand in awe of the majesty of a wave, the surfer is unique in his ability to appreciate its beauty and power. Whether standing on shore on a closeout day and watching a trackless wave destroying itself in thunder and spray, or seemingly flying across a wave that is changing from a wall to a tunnel, the ultimate realization of what waves are belongs only to those who have ridden them.

Categories: